Looking up at the night sky, we see the twinkling dots of light that are so familiar we forget how complex and distant they really are. For millennia, stars have been our compasses, our storytellers, and occasionally, the backdrop to romantic clichés. But what are stars, really? Not the twinkling myths or symbolic guides, but the physical furnaces that shape the very chemistry of our existence. To answer that, we need to go on a journey from the birth of a star to its eventual demise, and discover how we are (quite literally) made of stardust.

The Birth of a Star: From Dust to Fire

A star’s conception begins in an enormous cloud of gas and dust, known as a nebula. These clouds are so massive that they make our Solar System look like a single blueberry rolling around on a school playground, and yet, they are thin enough that if you flew through one in the Millennium Falcon, you might not notice.

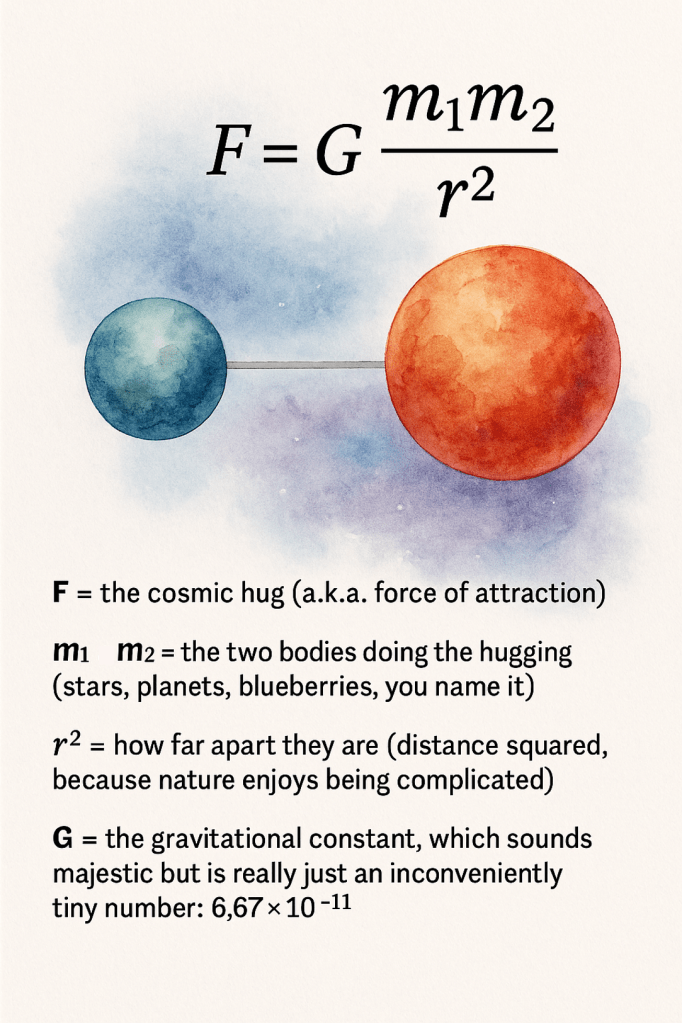

Why do things even happen at all inside a nebula? That is thanks to gravity, pulling particles of gas and dust towards each other.

In essence, everything in the universe is trying to hug everything else. The bigger and closer you are, the tighter the hug. In a nebula, that hug eventually gets awkward enough to pull lumps of gas together. The gas compresses, heats, and eventually reaches a temperature of approximately 10 million °C. At that point, the atoms give up resisting, and fusion begins. A protostar is born, but it is still hidden in its dusty cocoon.

A quick recap of Newton’s Law of Gravity:

Newton’s law of gravity says that every object in the universe pulls on every other object. The bigger the objects are, the stronger the pull. The farther apart they are, the weaker the pull.

In plain English? Gravity is the invisible glue of the cosmos: it keeps planets in orbit, holds moons to their worlds, and ensures that apples fall politely downwards instead of drifting off into space.

Stellar Nurseries: Where Stars are Born

Stars are like a litter of cosmic kittens, and they do not tend to pop into existence as a solo act. They are born inside enormous giant molecular clouds (GMCs), which span up to 300 light-years across. For comparison, our entire Solar System is less than a light-day wide!

Material starts collapsing unevenly inside these clouds. Long filaments form, with dense knots strung along them like pearls on a string. Each knot is a protostar, a baby star wrapped in gas and dust, waiting until it is hot enough to shine.

As the gas collapses, it gets hotter. Normally, hot things expand, but hydrogen molecules inside the cloud act like tiny air conditioners. Instead of puffing outward, the heat goes into splitting molecules apart, allowing the collapse to continue.

Lighting the Furnace

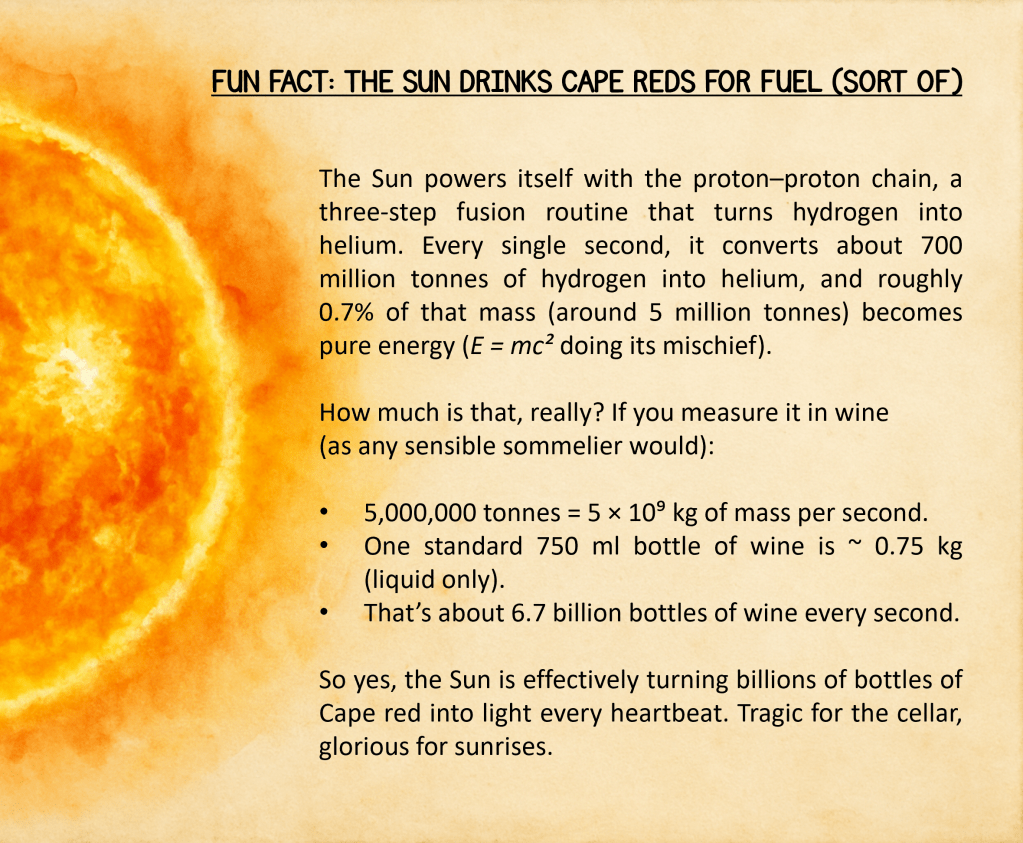

Eventually, the core becomes so hot, about 10 million kelvin (physicists prefer to measure in Kelvin as it starts at absolute zero), that protons buzz around at hundreds of kilometres per second. They then collide so violently that the strong nuclear force overwhelms their mutual dislike (both being positively charged). Fusion begins, and a star is born.

Stellar Siblings, Clusters, and Galactic Nebulae

Stars are rarely “only” children. A single cloud may produce hundreds or thousands at once, glowing in a variety of colours from massive hot blue giants to cooler red dwarfs. Over time, the bigger ones blow the gas away with radiation, leaving behind open clusters like the Pleiades, a group of stars still hanging out after 100 million years, the galactic equivalent of a high-school reunion that never ends.

Star nurseries also create some of the prettiest things in space: galactic nebulae.

- Emission nebulae glow pink as baby stars excite hydrogen gas.

- Dark nebulae are so dense they block starlight.

- Reflection nebulae scatter starlight like cosmic glitter.

The Pillars of Creation in the Eagle Nebula show all three at once. It’s basically the maternity ward of the universe, only much prettier and considerably louder. Well, not to us in any case, since space has no air for sound to travel through, but if you could somehow eavesdrop on the shock waves and stellar tantrums in there, it would make a vuvuzela sound like a polite cough.

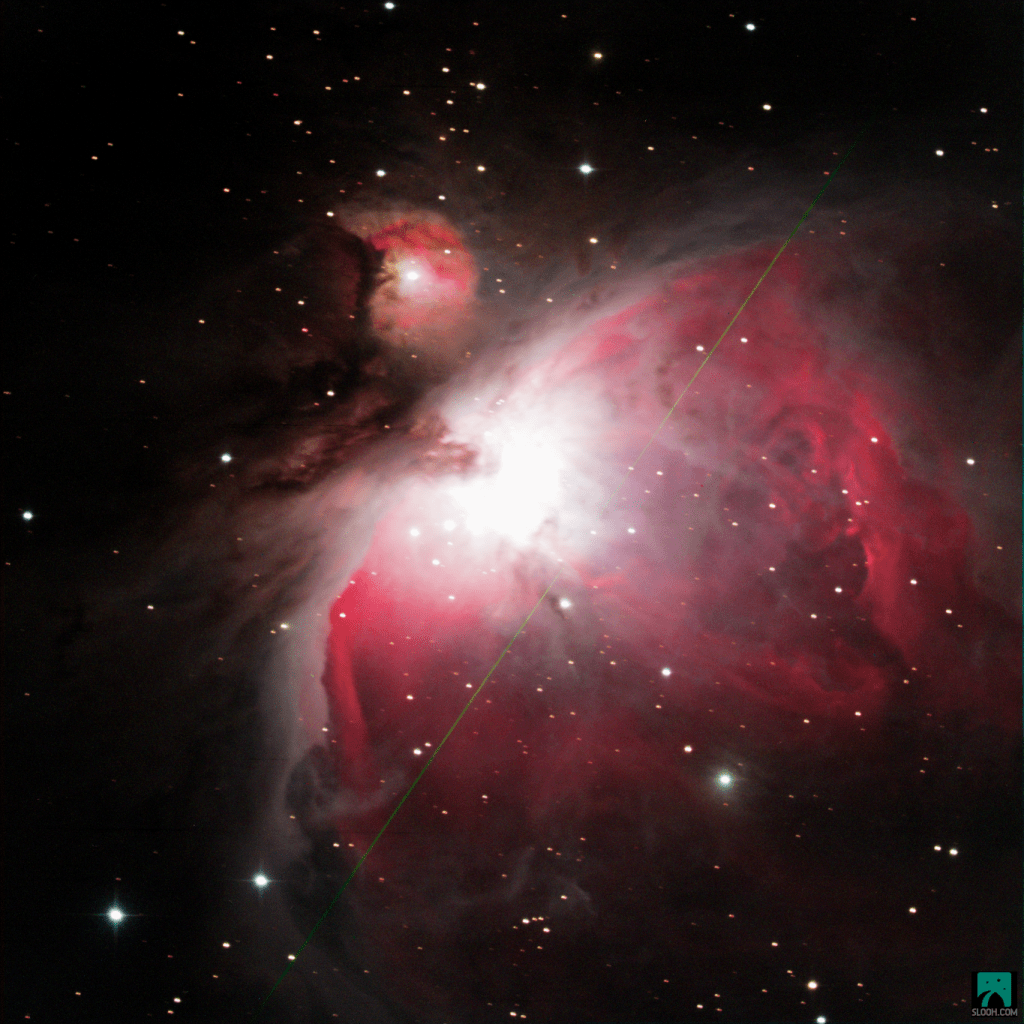

Emission Nebula:

Orion Nebula (M42)

Image captured using Slooh telescope network (© Slooh)

An emission nebula is a glowing cloud of gas in space that shines with its own light. The gas gets energized by nearby stars, especially hot young ones, and starts to glow.

Dark Nebula:

Dark Doodad Nebula (DCLD 301.0-08.6)

Image captured using Slooh telescope network (© Slooh)

A dark nebula is a cold, dense cloud of gas and dust that blocks the light from stars and glowing nebulae behind it. It doesn’t shine or reflect light, so it looks like a dark patch in space.

Reflection Nebula:

Running Man Nebula (NGC 1977)

Image captured using Slooh telescope network (© Slooh)

A reflection nebula is a cloud of space dust that doesn’t shine by itself, but becomes visible when light from nearby stars bounces off it. The dust scatters the starlight, often making the nebula look blue and misty.

Balancing Act

Once a star lights up, it spends most of its life in a delicate standoff: gravity pulls inward, while fusion pushes outward. This state is called hydrostatic equilibrium and keeps stars stable for billions of years.

A star’s brightness can be estimated with the Stefan–Boltzmann law:

L = 4πR2 σT4

Where:

- L = luminosity (total power output of the star, in watts),

- R = radius of the star,

- σ = Stefan–Boltzmann constant ( 5.67 × 10-8 W m-2 K-4 )

- T = surface temperature of the star (in Kelvin).

This basically says: the bigger and hotter you are, the brighter you shine. In fact, if you double a star’s surface temperature, it gets 16 times brighter. Stars are not subtle.

How it works

- The Stefan–Boltzmann law tells us the power emitted per square metre of the star’s surface is σT4

- A star has a surface area of 4πR2. Multiply them, and you get the star’s total brightness.

Therefore, If you know the radius and temperature of a star, you can estimate its total energy output. Just like that!

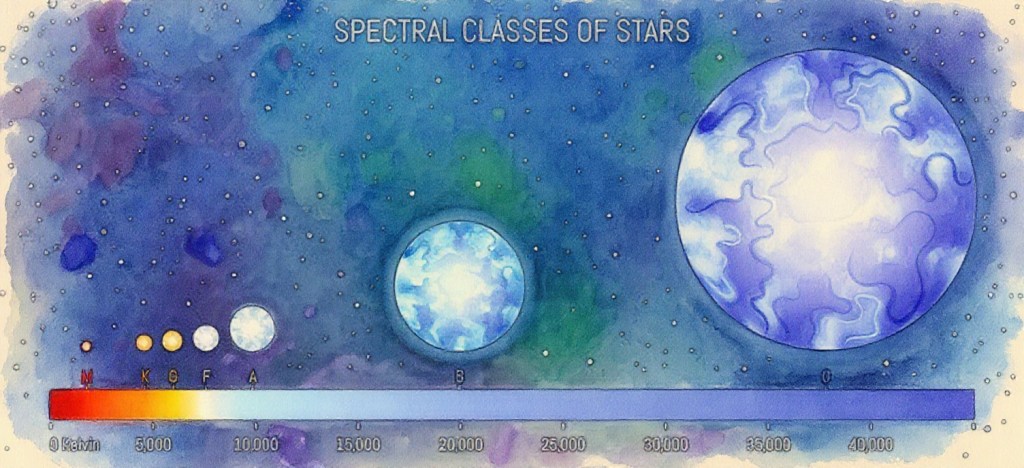

Star Classes

When astronomers talk about star classes, they usually refer to the spectral classification system. This is a way of sorting stars based on their surface temperature and colour, which also relates to the types of absorption lines we see in their spectra.

Spectral Classes:

| Class | Colour | Temperature Range (K) | Examples | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| O | Blue | 30,000 – 50,000 | ζ Puppis, θ¹ Orionis C | Extremely hot, massive, very luminous; ionised helium lines in spectra |

| B | Blue-white | 10,000 – 30,000 | Rigel, Spica | Strong helium lines, some hydrogen |

| A | White | 7,500 – 10,000 | Sirius, Vega | Strong hydrogen Balmer lines |

| F | Yellow-white | 6,000 – 7,500 | Procyon | Metals (Ca II) and hydrogen lines |

| G | Yellow | 5,200 – 6,000 | Sun, α Centauri A | Strong ionised calcium, metals; moderate hydrogen |

| K | Orange | 3,700 – 5,200 | Arcturus, Aldebaran | Neutral metals, weak hydrogen |

| M | Red | < 3,700 | Betelgeuse, Proxima Centauri | Strong molecular bands (TiO), very cool |

Here’s a summary:

- O-type: Enormous blue monsters, 30,000 K or hotter. Live fast, die young.

- B-type: Still very hot, still very blue.

- A-type: White stars (Sirius is one).

- F-type: Yellow-white, hotter than the Sun.

- G-type: Yellow stars like our own, around 5,800 K.

- K-type: Orange, cooler, very long-lived.

- M-type: Red dwarfs. Small, dim, but so common they make up most of the galaxy.

Essentially, stars live according to their waistlines:

- Skinny red dwarfs: trillions of years.

- Medium G-types like the Sun: 10 billion years.

- Chubby blue O-types: a few million years.

The Dramatic Deaths of Stars

Gravity hails its last victory as the star runs out of fuel. The beautiful nuclear fires sputter out, the delicate balance that kept everything together collapses, and what follows is a grand finale in full Spanish telenovela style. It is full of drama and utterly unapologetic.

The Sun-like stars swell into red giants, their outer layers drifting away like cosmic smoke rings. What remains is a glowing ember called a white dwarf: it is small, hot, and surprisingly still bright, and slowly cooling down over billions of years.

Massive stars, however, live fast and die violently. They collapse inwards and then explode outwards in supernovae so brilliant they can briefly outshine entire galaxies. These blasts forge gold, uranium, and other heavy elements, seeding the cosmos with the raw material for planets…and for us!

A star’s ending really depends on how heavy it is:

- Smaller stars (less than 1.4 times the Sun): fade into white dwarfs. They are tiny hot leftovers about the size of Earth, but still very heavy.

- Medium stars (1.4–3 times the Sun): They collapse into neutron stars, which are super dense objects only about 20 km wide. Just one teaspoon of neutron star material would weigh more than a billion tons! Some spin so fast they flash beams of light like space lighthouses.

- Giant stars (more than 3 times the Sun): They become black holes. These are places where gravity is so strong that not even light can escape. At that point, the rules of physics as we know them stop working.

Final Thoughts

From the birth of a star to its finality, there is a beautiful yet macabre twist, though: without these deaths, there would be no life…nothing. The iron in our blood, the calcium in our bones, the gold in our jewellery (and teeth?), they were all born in the last gasps of dying stars. In a very REAL sense – we are stardust.

OK, yes, we are walking around as recycled stardust, a temporary arrangement of atoms that were once scattered across space. But what was once dispersed across the universe in a dramatic spectacle is now gathered and molded into the shape of you (and an unfathomable amount of other things, too!).

So, what are stars, really? They are colossal balls of plasma, powered by fusion, ruled by physics, and draped in poetry. They are the universe’s chemists diligently forging elements; its architects, shaping galaxies; its midwives, welcoming in planets. They live extravagant lives and die spectacular deaths. In doing so, the cosmos is gifted with the raw material for everything, with the rare chance of creating something incredible: life.

The next time you look up at the night sky, remember that you are not just seeing the twinkling dots of light; you are looking at our family tree, from its beginning to the present.

Leave a comment